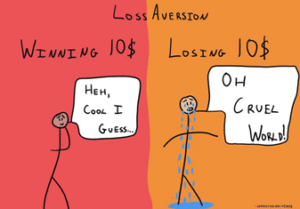

In the realm of decision-making, our minds often play tricks on us, subtly nudging us towards choices that minimize potential losses rather than maximizing gains. It’s a psychological quirk that transcends mere preference; it’s ingrained in how we perceive and react to the world around us. Imagine standing at a crossroads, where the fear of losing what we already have can outweigh the allure of what we might gain. This fascinating phenomenon, known as loss aversion, shapes everything from our everyday choices to significant financial decisions, shedding light on why we often tread cautiously even in the face of promising opportunities.

Loss aversion subtly shapes our behavior by making us prioritize avoiding losses over acquiring gains—even when the latter would leave us better off. Take gym memberships, for example. Many people continue paying monthly fees despite rarely attending. Why? Because canceling feels like locking in a loss—acknowledging that the money already spent has gone to waste. Instead of cutting ties, they hold on in the hope of future use, driven more by the desire to avoid feeling the loss than by a realistic plan to return. Similarly, in casinos, gamblers often double down after losing, not out of strategy, but from an emotional urge to “win back” what’s been lost—again, trying to avoid mentally accepting a loss. Even with FOMO, the fear of missing out isn’t always about excitement or opportunity; it’s often rooted in the anxiety of losing a chance, a connection, or a shared experience. Across these scenarios, people aren’t necessarily chasing gains—they’re desperately trying to avoid the sting of loss, proving how deeply loss aversion is wired into our decision-making.

Loss Aversion in Marketing and Consumer Behavior

This deep-rooted fear of losing isn’t just limited to personal choices—it’s something marketers have long understood and strategically leveraged to drive consumer behavior. Loss aversion plays a powerful role in advertising and pricing tactics, subtly influencing how people perceive value and urgency. Consider the ubiquitous “limited-time offer” or “only a few items left” messages. These aren’t just prompts—they’re psychological nudges, triggering the fear of missing out and framing the situation as a potential loss rather than a delayed gain. Consumers are more likely to act not because the product suddenly became more appealing, but because the idea of losing the opportunity feels worse than the benefit of waiting.

Pricing strategies also exploit this bias. Take price anchoring, for example: showing a product’s original price (₹199) next to its discounted rate (₹99) creates a mental reference point that makes the lower price feel like a gain and avoiding the higher price feel like dodging a loss. Similarly, subscription models frame cancellation as losing access to valued services—even if the customer isn’t actively using them—which discourages churn. Psychological pricing, like ending prices with .99, may seem trivial, but it plays on consumers’ tendency to see ₹9.99 as significantly cheaper than ₹10, softening the perceived loss of money.

In each of these cases, companies are not just selling products—they’re selling relief from the emotional discomfort of loss. By positioning their offerings in a way that frames non-purchase or cancellation as a personal disadvantage, marketers effectively turn loss aversion into a tool of persuasion, shaping consumer behavior in subtle but powerful ways.

Loss Aversion in Policy Making and Social Programs

Loss aversion doesn’t just show up in shopping carts—it plays a big role in public policy and social programs too. Governments have learned that people are far more motivated to act when they feel like they might lose something, rather than when they’re promised a gain. Take opt-out retirement savings plans, for example. Instead of asking people to sign up, they’re automatically enrolled—and most stay in. Why? Because opting out feels like giving up future financial security, and that loss feels more painful than the effort of staying in. Public health campaigns use a similar trick. Messages like “Don’t lose years of your life to smoking” hit harder than “Quit smoking and live longer.” By highlighting what’s at stake, rather than just what’s to be gained, these strategies tap into our natural tendency to avoid loss—and they work. Whether it’s health, money, or safety, framing the cost of inaction as a personal loss makes the desired choice feel like the only smart move.

The Role of Education: Equipping a Future-Ready Workforce

The solution doesn’t lie in resisting AI but in adapting to it.

India is taking bold steps. With AI projected to contribute $17 billion to its economy by 2027, initiatives like “AI for India 2.0” and “AI For All” aim to democratize access to AI literacy. These programs offer content in 11 languages, ensuring that rural and urban learners alike can participate in the digital economy.

Universities are setting up AI labs where students can build models, test algorithms, and solve real-world problems. Faculty members are integrating AI into coursework, moving from theory to application across disciplines—from ethics and policy to healthcare and business.

Stackable, modular credentials are replacing traditional degrees. Learners can now gain micro-skills in data science, prompt engineering, or robotics—keeping pace with a job market that changes every six months.

The goal is not just employability—it’s leadership. India is nurturing a generation of AI-native innovators who will shape, not just survive, the future.

Behavioral Finance and Investment Decisions

Here’s where it gets really interesting—loss aversion doesn’t just influence public policy; it also sneaks into your wallet and plays mind games with your investment decisions. In behavioral finance, it shows up when people hold onto losing investments far longer than they should. Why? Because selling feels like admitting defeat, and that psychological sting of a realized loss often outweighs the logic of cutting your losses and moving on. It’s not just about numbers—it’s about emotion. Then there’s the endowment effect, another sneaky bias that makes us overvalue what we already own. Investors often think their stocks are worth more simply because they picked them, not because they’re actually performing well. This inflated sense of value can lead to poor financial choices—like refusing to sell when it’s the smart move, or ignoring better opportunities. Whether it’s a stock portfolio or even something as simple as your house, ownership makes us biased. It clouds judgment, complicates negotiations, and, in many cases, keeps people stuck. Understanding these psychological pitfalls is key to making clearer, more confident investment decisions—and avoiding traps that feel safe, but aren’t.

Psychological and Emotional Dimensions

All this talk about how loss aversion shapes our choices—in policy, money, and daily behavior—naturally leads us to a bigger question: why are we wired this way in the first place? To really understand the grip loss aversion has on us, we need to explore the emotional and psychological mechanics behind it.

At its core, loss aversion taps into the brain’s hardwired response to pain—specifically, the pain of loss. Neurological studies using tools like functional magnetic resonance imaging (FMRI) show that the brain reacts more intensely to potential losses than to equivalent gains. In fact, the areas of the brain associated with pain and fear—like the amygdala and insula—light up significantly when people anticipate losing something. It’s not just an abstract discomfort; your brain processes a financial loss similarly to a physical threat.

What’s even more fascinating is that not everyone experiences loss aversion the same way. Individual differences in susceptibility have been traced back to variations in brain structure and function. Some people show stronger activity in neural circuits linked to emotional regulation, making them more sensitive to potential losses. Others have more balanced or resilient patterns, which may explain why they’re better at managing risk and uncertainty.

Culture also plays a role. In more collectivist societies, for example, the fear of letting down the group can amplify loss aversion, whereas in individualistic cultures, personal failure might be the bigger driver. How we’re raised, what we value, and even the economic environment we live in—all shape how deeply we feel the sting of loss.

But here’s the good news: it’s not all hardwired. People can learn to manage their responses. Mindset shifts—like reframing decisions in terms of long-term growth rather than short-term loss—can help. So can coping strategies like practicing mindfulness, journaling to track emotional biases, or using decision-making frameworks that emphasize objectivity over instinct. Understanding that loss aversion is as much about emotion as it is about logic can be the first step in loosening its grip—and making smarter, more confident choices in every area of life.

Counteracting Loss Aversion

Counteracting loss aversion starts with awareness—and then action. Behavioral coaching and financial literacy programs can help individuals recognize when fear is driving their decisions and teach them to reframe losses as valuable learning experiences rather than failures. Simple tools like decision journals, automated savings plans, or checklists for evaluating choices can build habits that encourage rational thinking over emotional reactions. Ethically, there’s a fine line between using loss aversion to motivate and using it to manipulate. Smart companies understand this and design choice architecture that nudges consumers without trapping them—helping them avoid decision paralysis while still keeping the power in their hands. Ultimately, fostering consumer awareness and empowerment ensures that behavioral insights are used to support better outcomes, not exploit vulnerabilities.

Future of Behavioral Design and industry examples

We see real-world examples of loss aversion everywhere—from how products are marketed to how services are sold. Take insurance advertising, for instance. Companies rarely highlight the benefits of peace of mind; instead, they use phrases like “Don’t be left unprotected” to tap into the fear of future loss. The emotional pull is stronger when the message frames what you could lose rather than what you might gain. In the world of retail and branding, Gymshark and Nike offer a compelling contrast. Gymshark leverages scarcity and hype—limited drops, countdowns, and “almost sold out” alerts—to stir fear of missing out, a form of anticipated loss. Nike, on the other hand, often relies on emotional legacy and belonging, but still infuses urgency in its marketing. Both understand that making people feel like they might lose access, status, or opportunity is far more persuasive than simply promising a reward.

Looking ahead, loss aversion will likely play an even more sophisticated role in how we interact with markets and technology. Predictive models powered by AI are beginning to track individual loss aversion tendencies, personalizing financial advice and marketing strategies in real time. In emerging spaces like Web3, NFTs, and crypto, behavioral economics is becoming a core tool—shaping how platforms build trust, drive engagement, and frame risk in decentralized environments. Behavioral finance continues to reveal how deeply emotion influences logic, and understanding loss aversion is key not just for optimizing strategies, but for becoming more self-aware. While we can’t eliminate losses, we can learn to view them through a rational lens—turning every setback into an opportunity for smarter, more resilient decision-making.

Contributor: Team Leveraged Growth